[In a life full of quirky projects, David Lynch’s comic strip “The Angriest Dog in the World” still stands out. Similar to Dinosaur comics, a single strip, drawn by Lynch, provided a palette for a weekly dose of philosophy and weirdness, running from 1983-1992, when Lynch must have become too busy to continue. The strip ran in the LA Reader overlapping some of Lynch’s rise to tremendous fame, alongside Matt Groening’s Life in hell and Lynda Barry’s Earnie Pook’s Comeek. Truly the golden age of alternative comic strips.

With all the attention to and tributes to Lynch’s work after his death, I was lucky to run across (on FB) this account of working on “The Angriest Dog in the World” from Dan Barton, who was editor at the Reader back in the day. Shared with Barton’s permission, yet more proof of the wonder that was David Lynch the man and creator. – -Heidi MacDonald]

Dumbarton

Back in the 1980s, I was the editor of the Los Angeles Reader, an alternative newspaper published in Southern California. I was young, inexperienced, and a little out of my depth. I work with super talent every day on a shoestring budget. Some go on to greater glory, some do not. More details next time.

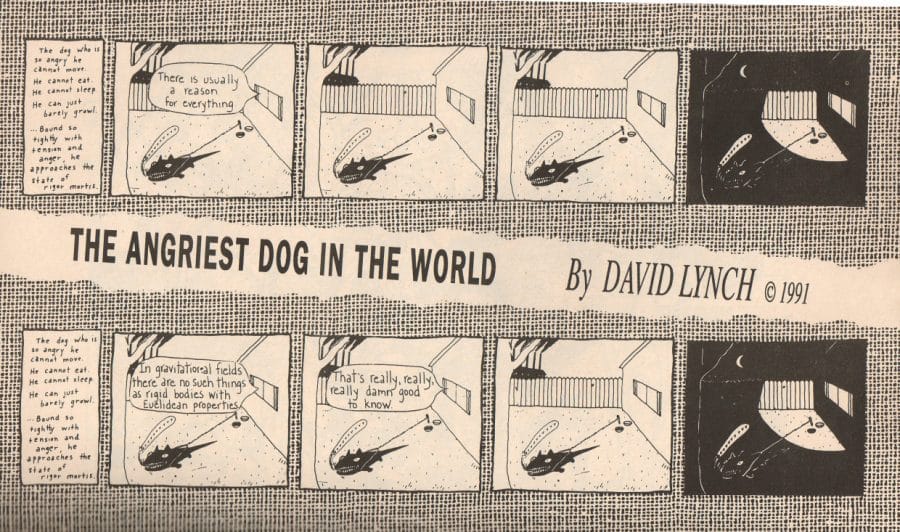

One of the regular features of “Reader” is a comic strip called “The Angriest Dog in the World” created by the author. . It consists of four panels, hand-painted in one sitting by Lynch. In the picture, a growling dog is chained outside the house, and its owner cannot be seen except for the subtitles floating out of the window.

Lynch submitted this artwork years before I arrived. Each week he provides subtitles over the phone. They changed every comic, but the art stayed the same. (This was before faxes, before email, before office computers.)

I heard a former Reader staffer say that Lynch’s weekly phone calls from the set of Dune were filled with static from the phone service in Mexico.

“Dogs,” as we called the strip around the office, was another feature of The Reader and part of its eternal weirdness: something that existed only in that particular publication.

When I became editor, Lynch would call me every week and provide subtitles. Sometimes he would delegate the task to an assistant, but for about a year and a half I had a weekly phone call with David Lynch.

When I became editor, Lynch would call me every week and provide subtitles. Sometimes he would delegate the task to an assistant, but for about a year and a half I had a weekly phone call with David Lynch.

The intercom on my desk would go off and the receptionist would say, “I’m David Lynch,” as if the pizza for lunch had just been delivered. I would pick up the phone and we would exchange pleasantries and he would say, “I got another dog for you.” I would write the caption and he would sign it. Our conversation didn’t last long at first.

Sometimes we talk about his movies. This is the first time I’ve seen his version dune. I rented the movie (which, believe it or not, was recorded on videotape), watched it in my apartment in Santa Monica, and then talked to him about it the next time he called. He’s not one to dwell on the past; he’s busy shooting another movie on the East Coast. but. . . He expressed regret that the special effects did not fully convey his purpose. I once asked him what that poisonous black liquid was? Kenneth MacMillan Baron Harkonnen poured water in a (literal) murderous rage. His answer was simple, in his special brisk way of speaking: “I don’t know,” he said, “but it works for him, doesn’t it?”

At one point, executives advised Lynch not to get paid to appear in the strip. “See if he’ll do it for free,” I was told. Lynch’s salary was meager: twenty-five dollars a week. For some reason, this became a particular point of contention.

When I handed Lynch this article, he laughed. “No,” he said. “You pay the price. It’s not free. I remember management was very disappointed when they heard the news. I was blamed. I asked Lynch the wrong questions.

My phone call with Lynch climaxed when he invited me to a screening. He told me he was in town working on his latest film: editing, scoring, and all the post-production duties. Then one day he asked me if I wanted to see it. I said of course. The next week, an assistant called back with a date and time for the screening. When he called about the strip show that week, I asked him if he would be there. We have never met. He said no, but he wanted to know what I thought after watching the movie.

The screening takes place at the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group studios. I remember the screening room was less than half full. There is a golden lion statue on each side of the screen. The golden lion is the company’s symbol. I think the screening room is on the Sunset Strip, but I’m not sure.

I brought a date. The lights dimmed and the movie started.

This movie is “Blue Velvet.”

I saw it a few months before it was released, before anyone knew about it. Now I realize I must have been one of the first people in the media to see it in its entirety, and probably the first people in the country to see it finished.

It was a mysterious and magical cinematic experience that I will never forget. Later that week, when David called me about the subtitles for that week’s strip, I hyped him up with genuine enthusiasm. In David Lynch fashion, he accepted every gushing compliment with a simple yet elegant “thank you.” When I asked him what the mysterious gas that Dennis Hopper inhaled from the canister through his mask was that caused him to have a bad temper, he gave me the same answer I’d heard before: “I don’t know,” he said. But it’s good for him, isn’t it?

Later that year, I left The Reader for a simple reason: I had sold my first novel. I received an advance based on the outline and sample chapters. It would be enough to live by the sea and write as much as you want for at least six months.

I remember the last time I spoke to David on the phone. I told him what happened and he perked up at the news. “Oh,” he said. “You have to do that.” And then he said goodbye, “It was a pleasure working with you.”

I met him again, in a supermarket in Westwood. His collaboration with Isabella Rossellini in “Blue Velvet” was unforgettable. I approached him and introduced myself. He smiled and said it was nice to see me in person. As he said goodbye, he grinned, winked and said, “Good luck, Dan.”

I never saw or spoke to him again. I remember a few years after leaving The Reader, the most watched TV show in the country was Twin Peaks, a show that captured the imagination of viewers with its light-hearted plot, stunning visuals and offbeat characters.

I guess these are the lessons I learned from talking to David Woodland: Never write for free. Do it the way you see it. Don’t be afraid of failure. You don’t need to know all the answers. Most importantly, work. create. Take it out.

Goodbye, David Woodland.

The World’s Angriest Dog was released in 2020 in a limited edition of 500 copies.