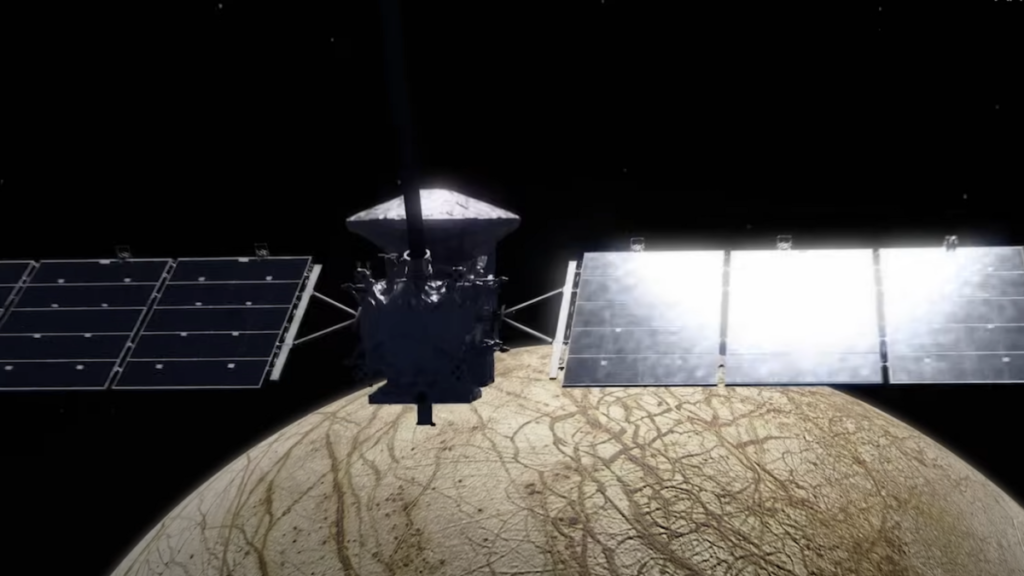

NASA’s probe, as long as a basketball court, is heading to the alluring planet Europa.

Planetary scientists believe Jupiter’s moons have deep oceans. A looming question is whether it possesses the ingredients and conditions to sustain life. The large spacecraft, the largest probe built by NASA for planetary science missions, has conducted about 50 close flybys of Europa in an effort to find answers about Europa.

“This is probably one of the best places beyond Earth to look for life in the solar system,” Cynthia Phillips, a NASA planetary geologist and project scientist for the space agency’s Europa Clipper mission, told Mashable.

NASA scientists view the first Voyager images. What he saw made him shudder.

The mission’s launch window will open soon, on October 10, when it will launch from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. If NASA finds that Europa is a habitable world, a second Europa mission will return, this time landing there to see if it is habitable. inhabited.

This image compares the size of the Europa Clipper spacecraft to a basketball court.

Image source: NASA

Why is the Europa Clipper spacecraft so big?

At more than 100 feet (30.5 meters) long, the Europa Clipper is massive because it needs to generate solar energy in deep space. Jupiter’s regions receive only three to four percent of the sunlight that Earth receives. Hence the long wings or arrays.

“You just need these huge solar arrays to power all your instruments,” Phillips explained. “We’re talking about large-area solar arrays.”

NASA explains that capturing distant sunlight will generate about 700 watts of electricity, “about the amount needed to run a small microwave or coffee maker.” But the spacecraft also carries batteries to power many lunar exploration instruments.

“I’m very excited about the payload we’re bringing to Europa,” Phillips said.

“I’m very excited about the payload we’re bringing to Europa.”

Ice-penetrating radar will probe beneath the moon’s icy, cracked crust. It will learn how this icy underground is made of, and possible, possibledetecting the intersection of ice and ocean. (Europa’s icy crust may be 10 to 15 miles, or 15 to 25 kilometers thick.) This radar can detect about a half-mile deep, or possibly deeper—depending on how broken up the ice is and how pure it is. (For example, a cracked underground means radar signals will bounce more off instead of penetrating downward). However, the radar has the potential to penetrate as deep as 19 miles (30 kilometers).

One of the Europa Clipper wings unfolds at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Image source: NASA

Europa Clipper’s Surface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) will collect particles ejected into the space around the moon.

Image credit: NASA/CU Boulder/Glenn Asakawa

In addition to a suite of specialized cameras, the Europa Clipper also carries an instrument called the Surface Dust Analyzer (SUDA), which can sample Europa particles ejected into space by tiny meteorites. “Micrometeorites continue to blast fragments of Europa’s surface into space,” NASA explains. “The individual ejecta are small, but scientists estimate that half a ton (about 500 kilograms) of Europa’s surface material is always floating above the moon.”

Mix and match speed of light

One of the mission’s most exciting opportunities – although far from guaranteed – is the possibility of the spacecraft flying through plumes of water ice erupting from Europa’s surface. This will allow instruments to provide precise insights into Europa’s interior.

“We would love to fly through the plume,” Europa Clipper project scientist Kurt Niebuhr said at a news conference before the mission’s launch.

“We’d love to fly through the plume.”

Plumes or not, mission scientists believe that approximately 50 close flybys of Europa’s surface will provide sufficient observations to demonstrate whether life is possible on Europa. Of course, it almost certainly has water. But all life requires energy: can this ocean world provide it? Does it contain basic chemical components like carbon that form the building blocks of life as we know it?

And, if all of these conditions are met, is there evidence that the ocean has existed for billions of years, providing a stable environment for life to evolve and sustain in the Europa Dark Sea?

Why scientists think Europa has an ocean

The Europa Clipper mission is an expensive scientific undertaking, costing approximately $5 billion. But NASA believes this Jupiter moon may contain fascinating oceans twice the volume All the oceans on Earth.

Why?

“It’s a great detective story,” Phillips said.

“It’s a great detective story.”

In 1979, the Voyager 2 spacecraft captured the first detailed images of Europa, showing that its surface is covered with criss-crossing cracks. Many of these lines are red, indicating that something is welling up from beneath the surface and filling them. Planetary scientists also know that as Europa swings around the gravitationally powerful gas giant Jupiter, its interior is stretched and pulled, a process that generates heat in the world. This tug may have provided Europa with heat for billions of years.

“This makes Europa very, very interesting,” Phillips points out.

An artist’s impression of oceanic and geothermal energy sources that may exist beneath Europa’s thick icy shell.

Image source: NASA

The surface of Europa as captured by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft.

Image source: NASA

Then, in the 1990s, NASA’s Galileo mission captured the legendary view of Europa’s chaotic, ridged surface, which suggested water near the top. More importantly, the spacecraft detected strong magnetic signals from the moon. Salt water is a very good magnetic conductor and can provide this signal.

“Galileo showed that Europa was more interesting than imagined,” Philip said.

“It’s a great detective story.”

The evidence keeps mounting. The Hubble Space Telescope has repeatedly found evidence of water jets erupting 125 miles (200 kilometers) above Europa’s surface. It all adds up. “There is probably a subterranean ocean on Europa,” Phillips said.

If it remains somewhat stable over many centuries, it may harbor conditions suitable for the development of life. We won’t know until we get there in 2030.

“This is a journey into the unknown,” said Nicola Fox, head of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.