owned by tribe Great Oak Press Founded a decade ago by California’s Pechanga Tribe, it provides a way to cultivate and expand knowledge of Indigenous voices. The publisher will attend San Diego Comic-Con on July 26, 2024, to promote two titles in its repertoire and discuss language revitalization plans through: Chag Lowery graphic novel, unknown soldier.

Director and Editor-in-Chief of Great Oak Press Lauren Niezgorzki and Kumeyaay artist Johnny Bell Contreras Hosts “Writing Their Reality: California’s First Native Publishing House,” which includes Lowery as well as writers and editors davolos family and Leave it to Macaro People of the Pechanga tribe.

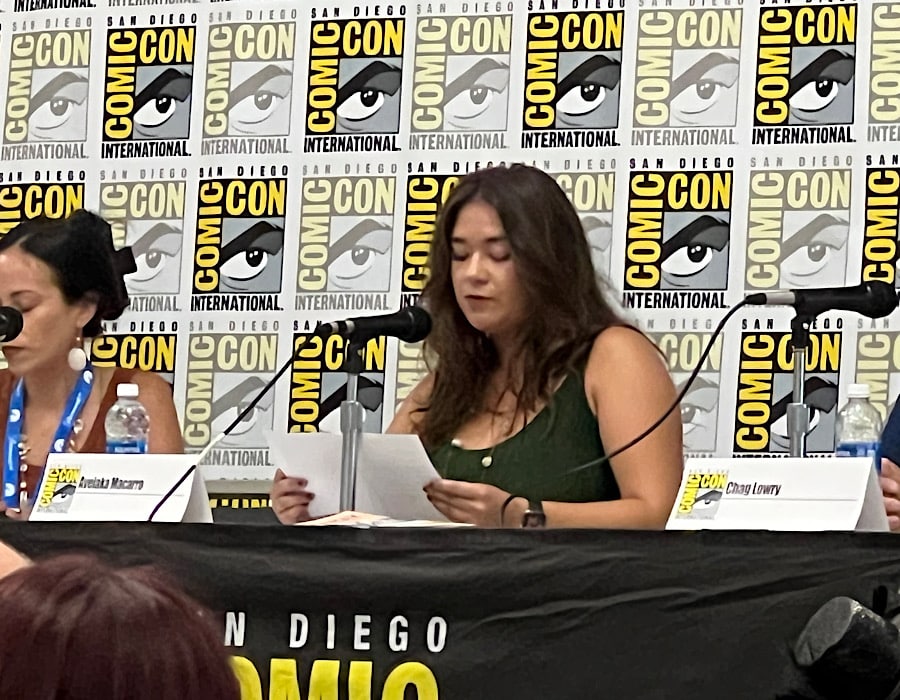

Macaro kicked off the discussion by reading the author’s “Rebirth” Marlene Dusek of Pass through Pay-mkawichum, Kumeyaay-Ipai and Cupa before embarking on the mission of the Great Oak Press.

“One of the things that’s completely different is that our editorial board is made up of people from the cultural resources sector who help sensitivity readers, fact-checkers, language users, Aboriginal studies professionals,” Niezgodzki explains.

“Our executive committee is made up of the Tribal Council, so we look to them for guidance and approval and moving our project forward. One of the truly unique things about our media is that we are not recruited for profit. We were created because We have a mission in mind to create a platform for Aboriginal writers and artists. Our main goal is to advocate for Aboriginal voices and publish work that matters to Aboriginal people.

As a Native American Studies major Most of the course readings at California Polytechnic State University, Humboldt, focus on Northern California Aboriginal culture. Recognizing an opportunity to fill a gap in resources in Southern California, Davolos returned home and came to Great Oak Press with a mission to elevate the history of Native women in Southern California.

“I’ve heard some of our native people say that the native people of Southern California no longer have culture. This is really hurtful and wrong. If they think and say that, what do non-natives think and evaluate? What about ours? So, that’s it. yesexistFather What emerged was the realization that we needed more perspectives and primary source materials to process our voices and tell the stories of our joys, our triumphs, our true histories and everything in between.

According to Macaro, yesexistFather It took five years from initial concept to production, with Macarro, her cousin Rebecca Macarro and Davalos working remotely, gathering stories via text messages, Facebook and Instagram. The work allowed the trio to reconnect with their tribal roots, while Great Oak Press allowed them to retain control of the narrative being produced.

“Right now, there’s a big push for local representation. Marvel has two local characters. There’s a push online for Wolverine to be localized because he’s from Canada. Because he’s from Canada, there’s a chance he could be aboriginal. That’s a big deal for me. It’s a deal, but it’s still constrained by a huge budget given the media coverage,” Macaro said. “This is important to us because it has a huge impact on our production capabilities and the care we take for the people who buy from us.”

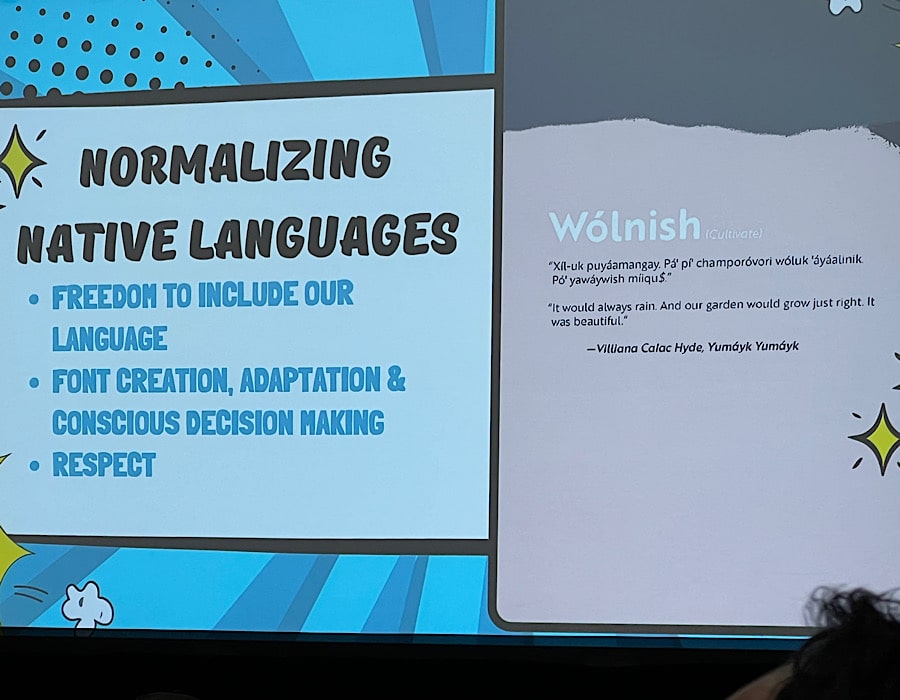

Davolos spoke of how Nizgorski encouraged the three to speak their native Walnish language, all out of respect for the people’s culture and perspectives. Part of the process involved hiring linguists, typeface creators, and tribal printers to add special characters to more accurately reflect the complexity of the language. Davolos believes this is what sets Great Oak Press apart from other publishers.

“It’s very important to us to find ways to live the language and ways for families to respect the language. It’s also part of the organization, part of the idea of telling our own stories, using our own language is an important part of our ability to maintain and nurture it respect for the ancestors,” Davolos said. “It’s about cultivating the idea of not just protecting it, but letting it grow in a different style, in a different way, and develop something.”

Davolos believes that documenting the language is important to preserve cultural heritage destroyed by Western civilization and as a way to restore their collective voice. Lowery goes even further to highlight how this language reflects larger environmental issues and the impact of government policy in defining land relationships.

Lowery’s graphic novel looks at the intergenerational relationships between Aboriginal people and their families who have served in the military since World War I.

“It always surprises me that Native Americans were not U.S. citizens at that time,” he explains. “So, I’ve worked with artists [Rahsan Ekedel] It took over three years to create this book, and I happened to meet Lauren at the end. I really appreciate her relationship with the press because I don’t care about publishers. I create my own work and people are my editors.

As Aboriginal people, we deserve to own every aspect of the structure that generates our stories, but for too long we have been unable to own that structure. So, this is very historic.

and unknown soldier, Lowery and Nizgorzki concentrated on not “alienating” the language. They wanted to preserve the language and allow readers to experience storytelling through a combination of pictures and text. Great Oak Press implements this philosophy into many of its projects.

“We develop a lot of children’s books, and as Chug said, these are not vanity projects. We create these books intentionally,” Niezgodzki said. “These books are used in the English schools where we book our children. The teachers have to know the language to teach us. But we don’t stop there. We are always in discussions with the school district. We are working hard to change the curriculum. That is our ultimate goal. We want to fix the narrative we pull from time and time again.“

Please pay attention for more SDCC ’24 The Beat reports.

related