The word “archaeology” conjures up countless images in the cultural imagination: ancient civilizations, lost artifacts, and—despite our attempts to move away from clichés—Indiana Jones. But one recent archaeological survey is unlike any other. This is done in space.

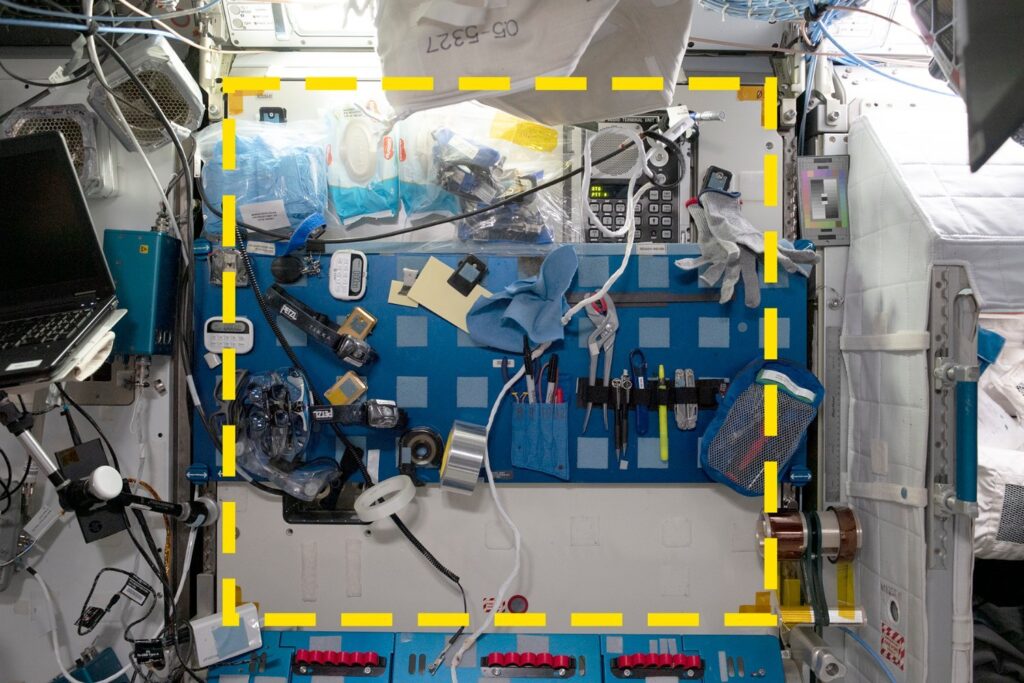

The archaeological survey, the Sampling Quadrangle Research Experiment (SQuARE), consists of six square survey areas on the International Space Station, approximately 254 miles (408 kilometers) from Earth. In a study published today in PLOS One, a team of researchers unveiled their findings at two sampling sites. One of the locations (pictured above) is the maintenance area of the International Space Station; the other is a comprehensive area near toilets and astronaut fitness equipment.

The team found that the way spaces are assigned meaning does not always match how they are actually used. During their 60-day survey, little of the maintenance area was used for maintenance and only a small amount was used for scientific purposes.

“It was actually a storage area, like a pegboard in a garage or garden shed,” said lead study author Justin Walsh, an archaeologist at Chapman University, founder and co-author. In this case, it is only possible because of the large amount of devil’s felt in this position.

“We realized that the historical photos showed something different because no one bothered to take photos of the workstation when no one was using it,” he added. “This is an important lesson about the relationship between historical photographs and long-term patterns of use.”

The program was launched in 2015 to conduct a retrospective review of how space on the International Space Station is used. But archival images could only show so much, so the team decided to conduct an archaeological survey exist station. After the team received approval from the International Space Station National Laboratory, it took less than a year to install the project on the space station.

“I think we’re probably one of the fastest payloads to go from proposal to execution in the history of the International Space Station,” said Walsh.

Fieldwork will take place between January and March 2022. Walsh noted that where astronauts can store their personal belongings “seems like an afterthought to the International Space Station, and it’s something that everyone who visits there has to deal with.”

So far, only two sample squares have been released, but the team plans to report findings from additional survey areas next year.

“There are some key takeaways. First, we show that good, productive archeology can be done in space even when investigators are on the ground,” said Walsh. “Secondly, we really showed that space in the space station is used in unexpected ways, which is a very human thing,” he added.

Like the countertop in my entryway is now called “where we keep our mail.” The ways of communication are varied and sometimes mysterious, but in my humble opinion, things should be named according to their specific purpose. Sometimes, however, spaces are assigned meanings (and labels) before it becomes clear how they are actually used.

“Finally, we provide useful insights that future space station designers can use to improve their habitats—we highlight important but not obvious phenomena,” adds Walsh. “Given that the International Space Station is probably the most expensive construction project ever built by humans, it’s important to learn from it and think about how to do it better.”

In fact, now is the time to plan how to improve future human habitation in space. When the International Space Station is scheduled to be decommissioned in 2030, it will deorbit and make a controlled crash landing in the Pacific Ocean. There are concerns that a commercial replacement for the International Space Station may not be ready in time before the legacy partners retire.

In addition to ongoing international space cooperation in orbit, there is the no small matter of the Lunar Gateway, a planned lunar space station that will establish a semi-permanent human presence on the moon. It’s bittersweet that archaeological work aboard the International Space Station will soon be more akin to traditional archeology, as the space station will soon become a thing of the past. If we are to learn lessons from how humans use research stations, now is the time.