The Cold War may be over, but all the wealth spent defeating the Soviet Empire wasn’t wasted when Loki only needed one punch. Photos taken by some very old US satellites may hold the key to finding humanity’s oldest man-made water systems.

A group of archaeologists from the Institute of Classical Archeology of Catalonia are interested in studying qanat, a water transportation system that dates back 3,000 years. Finding these ancient buried pipes was a challenge, so they came up with a novel solution: use something new (artificial intelligence) and combine it with something old (Stalin’s body wasn’t even cold when photographed satellite images) combined. These results provide a promising way to study the engineering capabilities of ancient civilizations.

The qanat “represents a remarkable ancient invention for sustainable water distribution in arid environments,” the archaeologists wrote in their study published in the journal Nature. journal of archaeological science. The system works by extracting water from underground sources in upland areas and flowing it along underground man-made waterways to open canals. Service tunnels were also dug to clean and maintain artificial waterways and allow air circulation. Qanat is found in most parts of the world, including China, the Iberian Peninsula and western China. Because of their often ingenious design, they are of great interest to archaeologists.

“These systems are extremely innovative,” Hector Orengo, a researcher at the Institute of Classical Archeology of Catalonia in Spain who led the study, told New Scientist. “They allow people to live in areas that were previously unimaginable.”

But ancient karats are also hard to find. In some regions, such as Afghanistan and Iran, volatile political situations can make it difficult to obtain images of the landscape where qanat is located. Previous studies using aerial imagery resulted in a large number of false positives due to a lack of resolution in the photos.

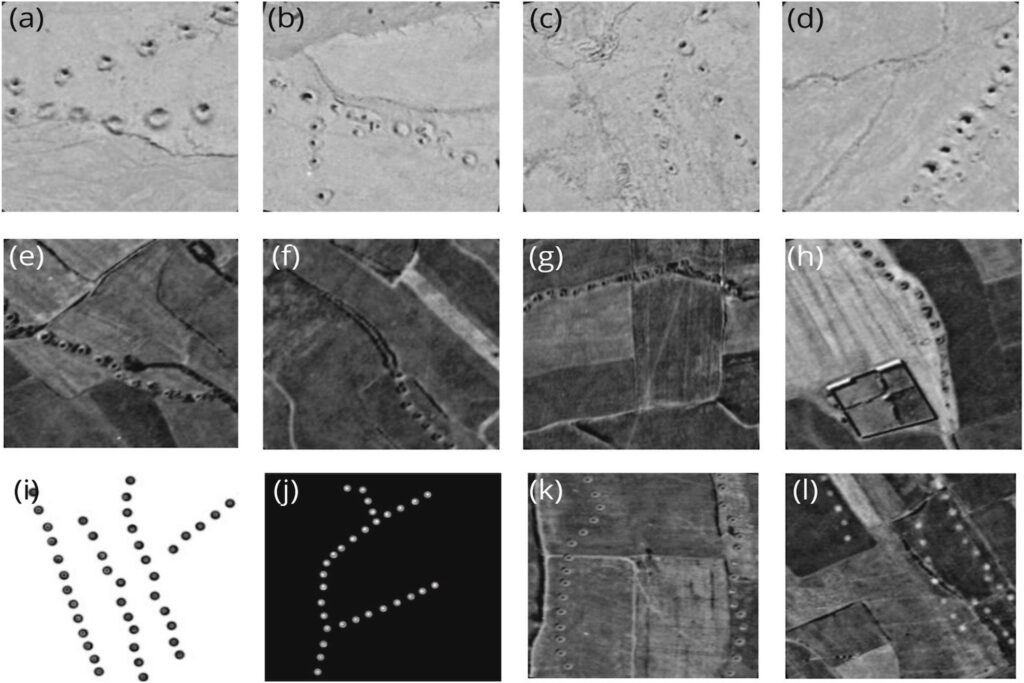

To solve this problem, scientists decided to test a new technology. They used a deep learning algorithm called You Only Look Once (yes, it’s YOLO) to analyze satellite images and examine the locations of discovered karats in Iran, Afghanistan and Morocco.

To obtain images, they turned to a rather outdated technology: the US CORONA and HEXAGON spy satellites. The former entered orbit in the late 1950s, while the latter was first launched in 1971.

Scientists trained YOLO to look for clues of karats in the ground, with each hole appearing as a black or white dot in the image. The artificial intelligence performed admirably, analyzing photos of abandoned satellites and finding more abandoned aqueducts. Their success rate in identifying karez was over 88%.

The system designed by the archaeologists has some significant limitations, requires a certain level of resolution to be successful, and can only operate with black-and-white photos. They also point out that the current version of artificial intelligence works best when studying desert areas (fortunately, that’s where most karats are located). They expressed hope that it could be expanded to other areas once more diverse training data is included.

Identifying qanat is not just a way for some archaeologists to obtain material for their next occult textbook. These waterways are valuable remnants of past civilizations, similar to Rome’s famous aqueducts. The qanat in Iran was even selected as a World Heritage Site. It turns out that Cold War-era satellites once used to determine the best spots to destroy America’s enemies can now also be used to preserve precious things.