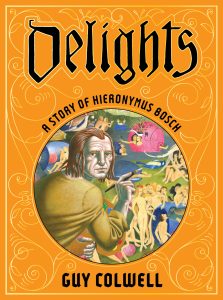

Fun: The Story of Hieronymus Bosch

Fun: The Story of Hieronymus Bosch

cartoonist: Guy Colwell

Publisher: Fanta Figure

Publication date: August 2024

Whether in life or in fiction, it is common to find stories of artists who saw visions. In the world of comics, the most obvious of which are William Blakewho transformed his vision of a god of reason, rebellion, and discovery into some great poetry and painting. There are seers there shakespearewhose verses shaped the future of their damned heroes and villains. In modern times, there is a delightful artist John VIIIwho use synesthesia to create brilliant color landscapes.

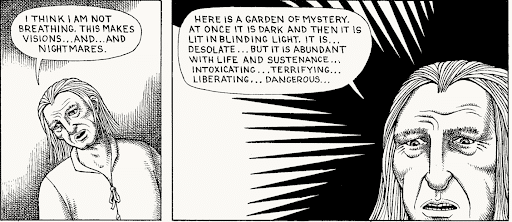

And, within the page Guy Colwell’s recent outing pleasurewe have another visionary: Hieronymus Bosch. Bosch was a man of few details, from which Colwell was able to paint an interesting picture. A man caught between his faith and the need to provide for his family has already courted controversy due to his aforementioned vision. However, we have only seen the tip of the iceberg of these visions. They blend into the reality of Bosch’s world without ever fully engulfing it.

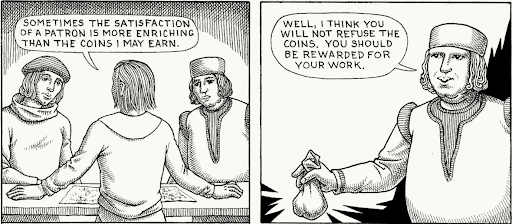

This may be the right decision. In stories about visionary artists, the focus is often on the vision and/or art. However, there is little emphasis on the act of working under the direction of a patron. But here, it’s still at the forefront of the story. When these stories of artists and patrons are told, there is often either reverence for the artist or antagonism. Here, however, Colwell offers something in the middle: criticism. It’s not that Bosch’s patrons hated his work, but they wanted something that religious painters found quite uncomfortable.

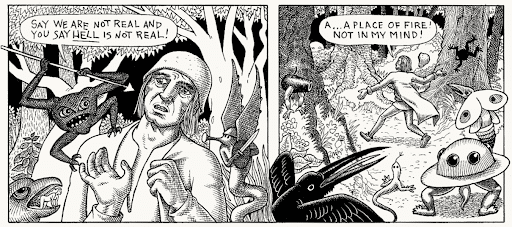

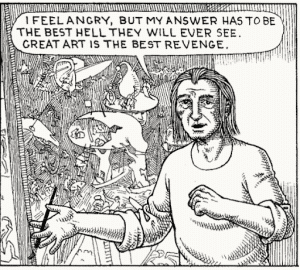

Sexuality is an undercurrent throughout the work, tracing the fine line between eroticism and sensuality. How can one participate in such art? Can one faithfully depict sin? What’s the line between a visionary and a madman? These questions were at the forefront of Bosch’s mind as he pursued his art. Colwell’s work depicts this tension in an admirable and gorgeous way.

Further emphasis is the artistic style employed by Colwell. In many ways, it feels like wood carving, with each line etched onto the paper with 15-inch precision mass.th The job of the century. With the limited background, in contrast to Bosch’s rather rich final design, we find a happy medium between the surreal and the real. This makes the scenes of heaven and hell even more jumpy.

Additionally, while the setting remains limited, the world always feels lived in. For example, consider the body language of two models and how it suggests a different type of relationship than the surface suggests. Or the rich costumes of the dukes who paid Bosch contrasted with and appealed to the simpler garments worn by the congregation of saints who questioned Bosch’s decisions.

Overall, this is a pretty good piece of work. Many times, one will find oneself short of words when talking about damn good writing on a subject with which one is unfamiliar. I am not a student of the full legacy of Bosch or Colwell. I was certainly interested in continuing to learn about their legacies, failures and successes. But that’s not who I am now. Even so, I understand the inner conflict of not being able to escape the customer’s desire to follow their own bird.

As a critic, I often find myself writing work that doesn’t entirely interest me just for the paycheck. As a result, I often find myself creating lower quality reviews and articles. I worked for Beat without pay, but was interested in Bosch’s life, albeit from an outsider’s perspective. I want to know more. We had a range of pieces to choose from and apply our craft to, I chose this one.

And, here and now, I find myself disappointed that I can’t find much more to say about this rather excellent work than what I have, so I end it with some rather opinionated remarks about the nature of criticism content to fill the space, and the only move against it is some pithy meta-commentary on doing so. Artists tend to approach their work this way. If criticism is not an art form, it is something else.

Indeed, it’s one of my favorite things pleasure: This does not mean that Bosch is above others. He is just one man, and his art-making faces the same conflicts and concerns that many artists might encounter. He is not that special person who uses art to save the world. His vision did not picture a future in which a utopia could be built. He’s not even a problematic person, and his problematic tendencies lead to great work. In fact, above all it was his piety that fueled his artistic engine.

Ultimately, this is why I recommend it the most. It rejects the clichés of the tortured artist in favor of something more honest. The pain, dear reader, is not in our vision, but in ourselves. Although Bosch was horrified when faced with his visions, the crux of his pain was his rejection of them, not that they harmed him or threatened him to harm others. Bosch remains a good man willing to fight for his art. Yes, he made compromises for his art. Because, after all, this is a worker’s field. It’s a job like any other. People really should be allowed to let the trust know what you are employed for.

Ultimately, this is a story about a man who knows he is a thing of the past. An era is coming that will forever change the way the world works. All of us, men and women, are victims of the vicissitudes of time. Era is something that is looked back to distinguish eras. We won’t know who will be affected or what will be affected until the dust settles. The future is always changing. We are cursed and saved by designs we can never truly see.

Ultimately, this is a story about a man who knows he is a thing of the past. An era is coming that will forever change the way the world works. All of us, men and women, are victims of the vicissitudes of time. Era is something that is looked back to distinguish eras. We won’t know who will be affected or what will be affected until the dust settles. The future is always changing. We are cursed and saved by designs we can never truly see.

Joy is available now.

Read more graphic novel reviews from The Beat!