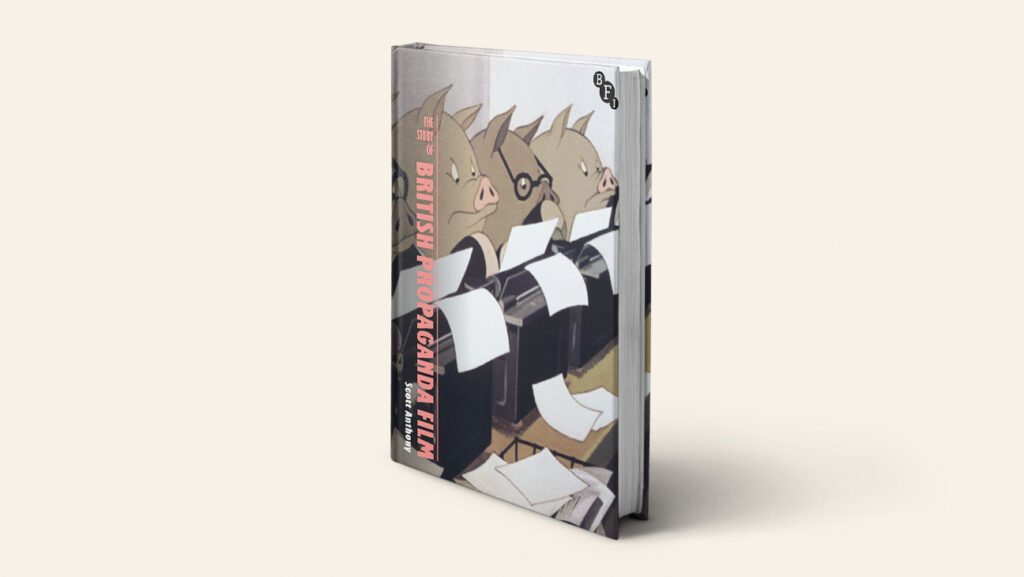

“All art is propaganda, but not all propaganda is art.” This quote comes from 1984 and animal farm Writer George Orwell in The Story of British Propaganda Videosis a new book in the British Film Stories series published by the British Film Institute (BFI) at Bloomsbury Publishing, and is written by Scott Anthony, deputy director of research at the British Science Museum Group (comprising five British museums).

This book, based on an archival project at the BFI National Archives, demonstrates the central role of propaganda in the development of British cinema and how it has shaped understandings of modern British history. While the term “propaganda film” is traditionally associated with wartime narratives, Anthony stresses that it did not end after World War I and World War II.

Instead, it became “a vehicle for packaging our cultural heritage, promoting tourism and transforming British culture”, the synopsis stresses. His argument: Propaganda is not always insincere or untrue. It can also highlight certain aspects of culture and act as a tool of soft power.

Dissecting classic examples of film propaganda, this book shows how the emergence of film as a global media phenomenon reshaped propaganda practices and how new propaganda practices reshaped the use of film and other forms of moving images. Battle of the Somme (1916), listen to the voice of britain (1942) and animal farm (1954), before discussing beloved film series such as james bond, harry potterand Paddington Movies and TV shows, and series like crowndigital media, etc.

Anthony believes that in an age of fake news, misinformation and disinformation, “the response to the ubiquity of propaganda films is often to produce more propaganda,” bringing us into what he calls “the age of total propaganda.”

The author has also previously published suspense novels Changidefines three periods or phases of British propaganda film. “This book describes how a promotional video transforms from a stand-alone object into an independent object – think about it triumph of will or Battleship Potemkin – form part of the broader media environment,” Anthony told THR.

This also means changes in scope and audience focus. In the history of British propaganda films, World War II was the period when the greatest number of classic, iconic independent propaganda films were produced. “For example, there are many movies about World War II or the Blitz that tell the story of what the war or the Blitz meant to the British people,” the expert explains. “But when you study it, you find that many of the most iconic films – e.g. There’s a fire — was made a year and a half after The Blitz. These films represent very painful events that have happened and play a role in shaping the audience’s response to it, not necessarily in a sinister way, but in a psychological processing way. You can think of it as an attempt to channel people’s energy. These independent films were screened in civic venues, canteens, military venues, union halls, and movie theaters.

In the second phase of the Cold War, “propaganda was seen as something other countries did, something only the Soviet Union and totalitarian societies did,” Anthony told The Hollywood Reporter. “Yet people realized they still had to respond to it. So they started making movies, trying not to look like propaganda films.

What experts are most concerned about is “essentially made for television, which operates in a more private, closed space or a personal space. Many of these films are about people who resist conformity, doubt or destabilize established careers.” . So they’re at a pretty subtle level,” Anthony explained. “I’m not saying they were insincere, but in a sense it was an individualistic propaganda. Part of it was anti-communist ‘Don’t be afraid to say no, don’t be afraid to doubt, the individual is the actual driver of history. ‘ and stuff like that.

Finally, the third period of propaganda films discussed in the final section of the book focuses on the world after the War on Terror. In the age of digital media, Anthony points out that the traditional definition of “film” no longer encompasses the full breadth and quality of promotional content. “You’re still going to make one-off promotional videos, but a lot of them are made for editing, memes or sharing,” the expert emphasizes. “A lot of the movies are actually not that interesting as individual objects, but they tend to be very, very common and show up in the news media or elsewhere.”

Anthony believes that in the first phase of British propaganda films, these films were rooted in shared experiences such as war, but now “digitization has expanded our geographical reach”. “A lot of people may be watching things on their phones very personally, not collectively, but also watching things that they themselves haven’t experienced or understand. So there’s this cycle that happens where a lot of digital media refers to itself Or to quote other digital media so it’s more of a round thing.

Scott Anthony

So what does Anthony mean by “the age of total publicity”? “When I say full propaganda, I don’t necessarily mean that it’s all lies,” he explained. “But I mean, really now it’s about the effort to shape information architecture or the information environment, rather than ‘I saw this movie about the NHS and I was inspired to believe it and use it. It. Rather, it’s more ‘let’s create a culture that anchors everyone,’ which is kind of all-encompassing.

At the same time, in this era of all-out publicity, driven by the wider availability and affordability of media technologies and tools, opening up content creation to more people, “there are now attempts to classify and shape who is who, and a credential ism’ and fact-checking: ‘This is true, not that,'” Anthony noted.

This is also consistent with an important finding of his research. “One thing I’ve discovered is that propaganda doesn’t always lie, it’s quite sincere,” he told us THR. “I think it’s more common than I thought. But in some ways the current trend is worrying because it’s moving away from personal films and toward shaping environments.

In the early days, government agencies often played a larger role in promotional videos. For example, animated movies animal farm Anthony stressed that the film, which began in 1954 and was directed by John Halas and Joy Batchelor, was adapted from Orwell’s novella and was partly funded by the CIA.

But he also points out that British propaganda films also often position Britain as a different actor than the United States and the rest of Europe. “Part of the story of America’s rise is that World War I devastated old Europe and cinema became an emerging global technology. Many countries in Europe began intervening in the film market, partly because they were worried. One thing you always hear is, cinema Basically the U.S. Embassy, all of our citizens will essentially become like U.S. citizens,” Anthony explained. “Governments are getting involved in Europe because they fear the United States will dominate this new media and shape their publics. At the same time, many of these countries are becoming democratic for the first time.

Experts say that in the UK the focus is on positioning “ourselves slightly upmarket within the Anglosphere” THR. “France can be a bit protectionist because it has French, but there is no option for language protectionism in the UK. So you have to do something else. You have to try to find a different way to differentiate yourself.

what to do harry potter, Paddington And other franchises that fit the theme of Britain harnessing its soft power in cinematic form? After the end of the Cold War, policymakers began to question the need to fund film production in the aftermath of a defining conflict around the world. The UK’s new Labor government, led by Tony Blair, established the British Film Council, which firmly believed “we need to market Britain’s global vision”, attract people to our culture, and attract visitors and tourists. . Therefore, promoting the UK and its cultural and creative output becomes even more important.

This is also the right place for 007 Anthony. “We fund movies that should support our global brands in the era of globalization,” he said. “As for James Bond, I mentioned that in the book because it made me realize that Britain was not a hard power country anymore. They weren’t really a military power, but they still enjoyed a high level of espionage. reputation. So people like it. [famous British computer scientist] Alan Turing, spies and deception are fascinating.

Anthony’s book also touches on the appeal of the British royal family and things related to it, e.g. crown. “The monarchy has played a huge role,” he said THR. With the post-war focus on democracy and modernization, British films reflected this. “In the UK, the monarchy has also gone through a re-modernization and you can actually see that in movies, for example in king’s speech. The monarchy is therefore an important part of how Britain sells itself abroad. and crown It has something to do with movies Queen Working with the same writer (Peter Morgan) who used the material. It’s essentially an upscale soap opera. It was great fun and I think it really helped sell the British vision overseas.

Where would King Charles III go? “I think it’s interesting that it’s actually part of the monarchy and part of Queen Elizabeth II because she left such an incredible mark,” Anthony said.