Jerry Seinfeld (the situation comedy character, not the real-life guy) is a successful, semi-famous comedian who lives in a Manhattan apartment approx. 800 sq. ft.

By comparison, Monica Geller and Rachel Green (in the first season of Friends) were a cook and a coffee shop waitress, respectively, living in apartments about four times the size of Jerry’s. twice as big.

Oh, and their place is always spotless and impeccably decorated.

And don’t get us started on how much free time they have to hang out with their friends!

We’re certainly not the first to observe that Friends offers an escapist, proudly unrealistic depiction of life in one of America’s most expensive cities.

To its credit, the show, like Sex and the City, at least occasionally touches on its characters’ financial woes.

But these brief hints usually come in the form of jokes or one-off, single-episode storylines.

Neither series is interested in truly engaging with the harsh realities of life under abject poverty.

Of course, these shows aren’t the only ones showing a lack of interest in money matters.

The story thrives on conflict, and most viewers can relate to the struggle to make ends meet.

Class struggle scenes in situation comedies

Yet modern television writers seem to have little interest in this near-universal aspect of the human condition. But this is not always the case.

We mention the difference between Jerry’s apartment and Monica and Rachel’s apartment because the years the two shows aired simultaneously marked a transitional period that was rarely discussed at the time:

Although “Seinfeld” and “Friends” each overlapped by several years on NBC, they were designed to appeal to different age groups:

“Seinfeld” was a show made by and for baby boomers who were then entering middle age.

Instead, Friends was written for bright-eyed, optimistic members of Generation X, many of whom viewed these characters as aspirational.

We could say that this was the beginning of television’s disturbing attitude towards working-class struggles.

A great time (at least on TV)

As the 21st century dawns, after decades of shows like All in the Family, Sanford and Son, and Roseanne, writers and networks suddenly seem insensitive to the struggles of those who find themselves at the bottom of the economic ladder Interested.

It’s no coincidence that the characters on Friends have risen through the ranks beyond most people’s wildest dreams:

(For example, Joey was promoted from long-term unemployed aspiring actor to daytime soap opera star.)

Like the sitcoms of the 1950s, the show is more interested in presenting an idealized world than a believable one.

You could call it a step backwards for the genre, but there’s nothing wrong with some shows taking such an idealistic approach – the problem arises when every show chooses to conveniently sidestep real life.

This problem isn’t limited to situation comedies, either.

Elite in the 10 p.m.

The hit TV series of the 2020s almost exclusively focused on doctors, lawyers, and police officers who never seemed to experience any financial setbacks.

Think of a show like Fire Nation, where at least half of the characters should Coping with financial constraints (firefighters and first responders are as poorly paid as teachers in this country).

However, we never see that other side of their lives on screen.

Last season’s biggest drama, Trackers , threatens to disrupt that trend.

After all, Justin Hartley’s survivalist character is Technically Unemployed.

But it seems that a life of fluid pursuit of rewards is a surprisingly profitable one.

So instead of a Steinbeck-esque modern-day vagabond, we have a hero who is a living testament to the joys and advantages of the gig economy.

The last gasp of socioeconomic realism

There have been very few TV shows lately that have made a real effort to portray the lives of Americans trying to do their best while worrying about next month’s rent every day.

The few shows that have shown interest in this segment of the population — like Showtime’s “Shameless” — have portrayed working-class people as cartoonish white-trash con men and criminals.

To be fair, there are some shows that still reflect an interest in the struggles faced by most working-class Americans.

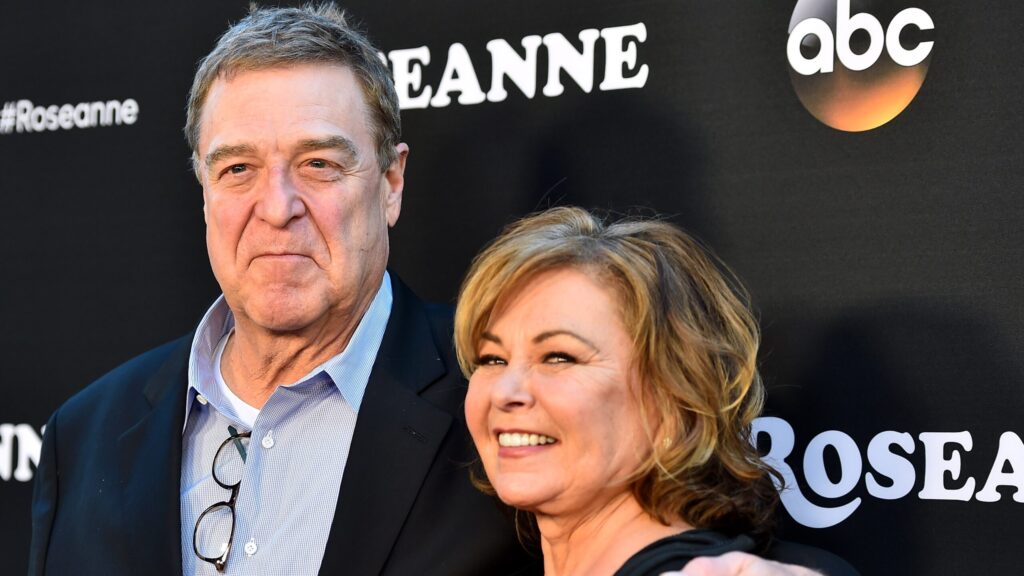

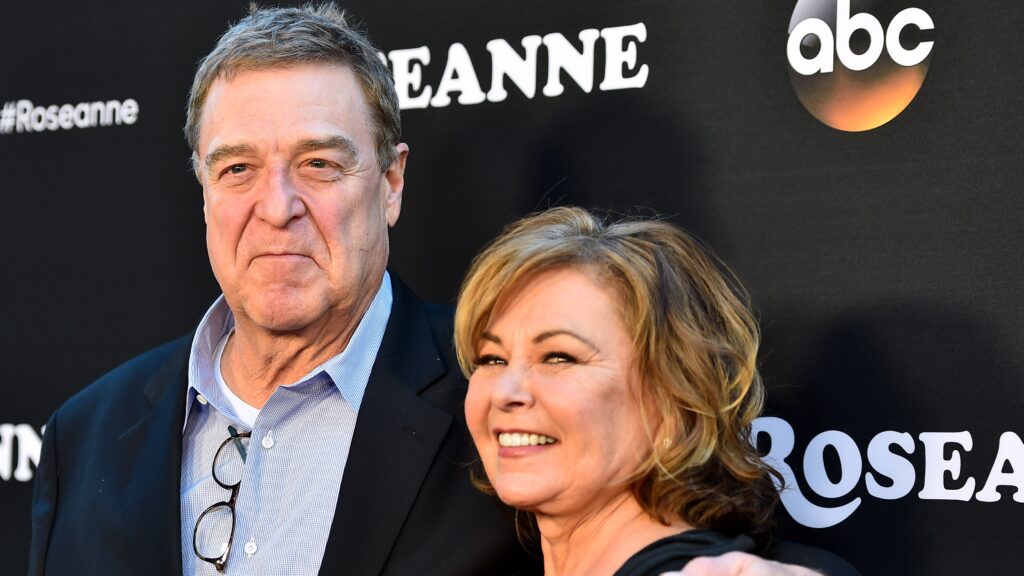

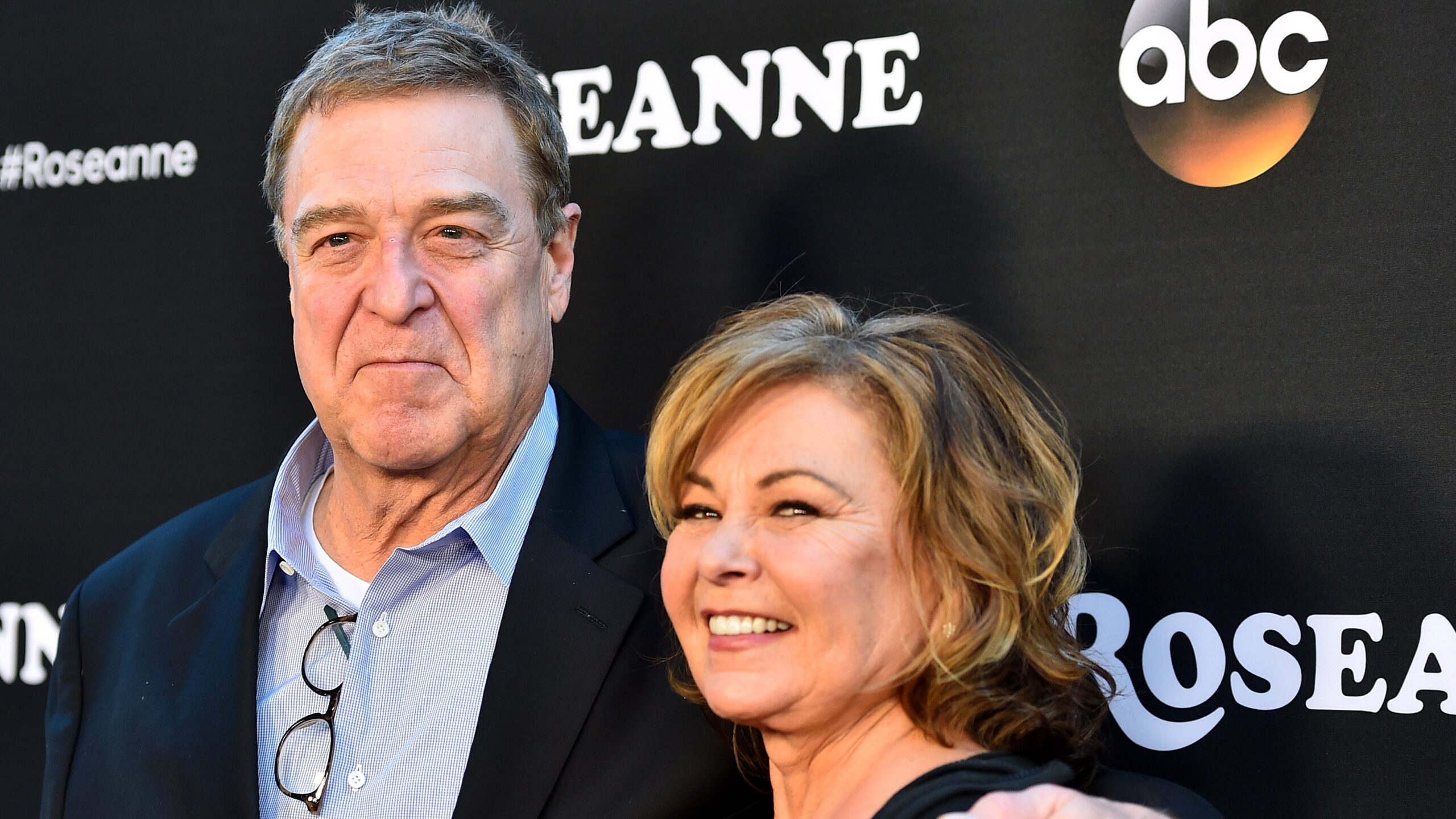

And, of course, there’s Roseanne spinoff The Conners — although that will soon wrap up with its seventh and final season.

There’s also Abbott Elementary, which grapples with the realities of a school plagued by budget problems trying to provide equal opportunity.

But such series are rare these days, a surprising development in an era and medium that otherwise reflects a refreshing, newfound interest in representation.

As is often the case with broad cultural trends, there is no single explanation for this phenomenon.

Typically, in this case, network executives are responding to popular taste while also shaping it.

You might think that in an era of record inflation and growing uncertainty about the future of the job market, Americans would embrace a television show that realistically depicts their current predicament.

But maybe the opposite is true.

Perhaps after a day of stress about the rising cost of living, the average viewer just wants to live vicariously through characters who don’t have such worries.

Writers did not entirely ignore economic issues.

Indeed, shows like Succession and Billions deserve credit for deftly threading the needle—commenting on the current state of American capitalism through poignant depictions of its victors.

In this way, they allow the audience to enjoy a bit of righteous indignation, a bit of class warfare while escaping reality.

Perhaps ultimately, seeing the merciless suffering suffered by the poorer classes of our country is too depressing for the average viewer.

But watching helpless people suffer when they shouldn’t have money? Well, that never goes out of style!

TV fans, what do you think? Do we need more socioeconomic diversity on television?

Hit the comments section below to share your thoughts!