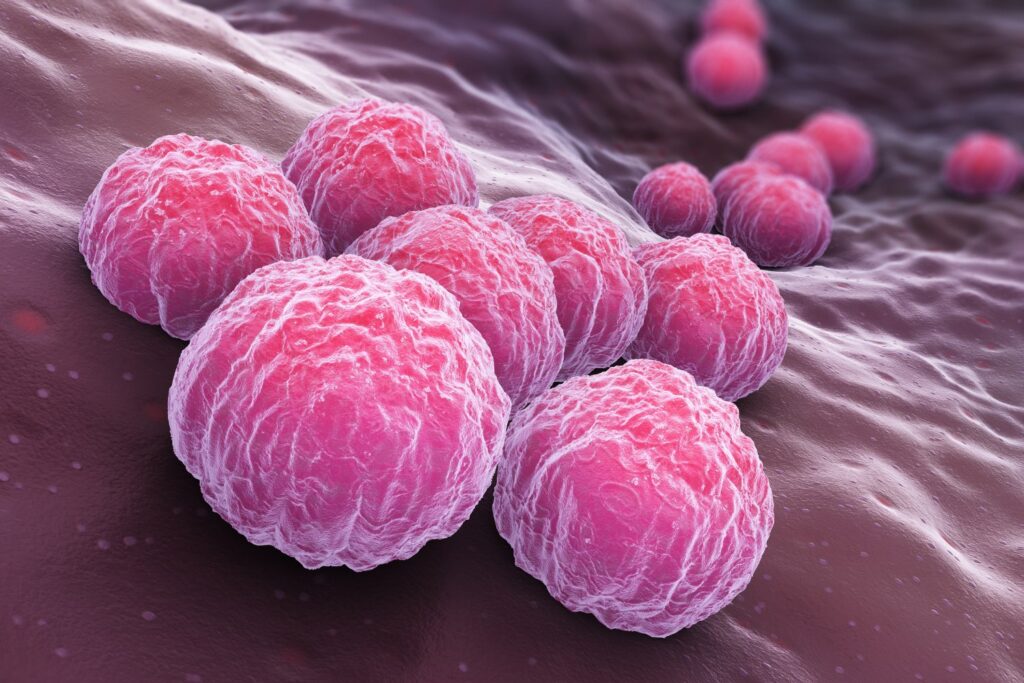

The bacteria that causes chlamydia may be trickier than we think. In a new study this week, scientists found evidence that these bacteria can hide in our guts. The researchers say the findings may explain why some people develop chlamydia infections again even after successful antibiotic treatment.

Chlamydia in humans is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (Other animals, including koalas, have their own versions). It is the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection in the United States, and by 2022, more than 1.6 million cases will be recorded. and other scary symptoms, depending on the infection. Untreated cases of chlamydia can lead to life-changing complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease, arthritis, and even infertility, while increasing the risk of contracting other sexually transmitted infections.

The new study, led by researchers at the University of Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, hopes to unravel a long-standing mystery about chlamydia. Although the infection can still be treated with antibiotics (at least for now), some people go to the doctor later with another chlamydial infection. When scientists study these cases, they sometimes find that people are reinfected by strains that are genetically identical or very similar to the bacteria that originally infected them.

Some of these cases may come from an infection that was actually not adequately treated, having sex with the same untreated partner who originally spread the infection, or playing with a sex toy that was contaminated from early use (this is less likely because the bacteria in We don’t live very long outside our bodies). But some studies also suggest that chlamydial bacteria can establish a hidden reservoir elsewhere in the body, allowing them to persist and cause trouble again when conditions are right.

Other related species Chlamydia trachomatis They are known to normally live in the gut of their hosts, suggesting that our chlamydial bacteria can hide there as well. But so far, studies showing that chlamydia may be persistent have mostly been done in animals. In the new study, published this month in the journal PLOS PathogensResearchers say they are closer to confirming that this condition does occur in humans.

Scientists grew human intestinal organoids (miniature versions of our organs or tissues) in the laboratory and then tested whether chlamydial bacteria could successfully infect them. These organoids are designed to resemble the layers of cells found in our intestines. Researchers found that bacteria are less good at infecting the “apical” surfaces of organoids, the layers of our organs that are exposed to the outside environment. But bacteria can easily infect intestinal organoids through the “basolateral” surface, or the layer of cells connected to other underlying tissues and structures, including blood vessels. When the researchers looked more closely at the bacteria infecting these organoids, they discovered a familiar enemy.

Lead researcher Pargev Hovhannisyan, head of the Department of Microbiology at the University of Würzburg, said in a statement: “In this case, we repeatedly found persistent forms of the bacteria, which can be clearly seen under an electron microscope through their typical shape. Identify these bacteria.

The researchers caution that these findings alone do not provide clear evidence that chlamydia can linger in our guts, so more work needs to be done to confirm and better understand this phenomenon. If this risk does exist, there are other questions that need to be answered, such as how exactly chlamydial bacteria get to the gut and the specific cells they like to hide in. But whatever we learn, it shouldn’t change how sexually active people protect themselves from these bacteria. Get tested regularly for chlamydia and other sexually transmitted infections (at least once a year, but possibly more frequently if you have multiple partners), consider consistent use of condoms or other barrier methods, and complete a full course of antibiotics if it is still important IMPORTANT: Chlamydia infection.